-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Chris D. Frith, Understanding madness?, Brain, Volume 139, Issue 2, February 2016, Pages 635–639, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv373

Close - Share Icon Share

The physical and the mental

The argument has been going on for a very long time. Is madness a spiritual/mental disorder or a material/physical disease of the brain? Two thousand years ago, most people, when confronted with someone foaming at the mouth and then descending into unconsciousness, believed that the person had been possessed by some spirit or God. They called this the ‘sacred disease’. In contrast to this view, Hippocrates wrote ‘It appears to me to be nowise more divine than any other disease, but has a natural cause’. The same distinction is made in the early modern period, but scholars now accept both causes. Felix Platter, who taught medicine in Basle in 1600, stated that melancholia could be ‘Natural, a certain effect so affecting the Brain, the seat of Reason’. He also wrote that it might prove to be ‘Preternatural proceeding from an evil Spirit’. And Robert Burton, in his Anatomy of Melancholy enjoins sufferers to ‘first begin with prayer, and then use physick’.

In the 19th century, the same distinction is found, although the terms have changed. Madness is no longer a spiritual disorder caused by gods, devils or sin. The contrast now is between physical and mental causes. For example, Philippe Pinel, the leading French alienist of his day, wrote ‘this form of insanity [delirious mania] has generally a purely nervous character, and … it is not the outcome of any organic defect in the substance of the brain’. This distinction was still important in the middle of the 20th century when I was taught to distinguish between physical disorders, such as organic psychosis (e.g. delirium) and psychotic depression (probably!), and mental disorders such as anxiety neurosis and reactive depression.

Pinel also concluded that, if madness is related to ‘an organic lesion within the brain’, then ‘the insane are left to look upon their sickness as incurable’. In contrast, a mental disorder will respond to ‘Moral Treatment’, although ‘douceur or kindness must always be backed by an imposing apparatus of repression’. The idea that brain disorders were incurable was overthrown with the advent of successful pharmacological treatments, in particular the serendipitous discovery of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs in the 1950s. While they may not cure, these treatments certainly reduce the severity of mental symptoms whatever their cause. Nevertheless, the distinction between physical and mental disorders remained. Brain disorders, such as schizophrenia, required physical treatments, such as drugs. Mental disorders, such as phobias, required psychological treatments, such as behaviour therapy. Furthermore, contrary to Pinel’s assumptions, it seemed that the brain disorders might be more curable than mental disorders as the development of some magic pharmacological bullet was always just around the corner.

Today, all these certainties and distinctions have been diminished. New techniques for studying the brain, such as staining and brain imaging, have revealed clear abnormalities in many disorders. For example, the presence in the brain of plaques and tangles in many cases of dementia was reported by Alzheimer in 1907. However, this and subsequent advances have only rarely been accompanied by the development of new treatments for psychiatric disorders. When appropriately prescribed, these antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs can give considerable benefits. On the other hand these drugs undoubtedly have distressing side effects and have frequently been over-prescribed. The backlash against this over-prescription of drugs and the failure to identify new approaches has led to many pharmaceutical companies abandoning research on disorders of the CNS (Miller, 2010). The other side has fared no better as the value of cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of psychosis has also been questioned (Jauhar et al., 2014).

Madness in Civilization: A Cultural History of Insanity, from the Bible to Freud, from the Madhouse to Modern Medicine By Andrew Scull 2015 Thames & Hudson, London ISBN: 9780500252123 £28

Today, we recognize how wrong we have been to make so much of Descartes’ distinction between the mind and the brain. There can be no worse insult for a neuroscientist than to be called a dualist. Unfortunately it is very difficult to overcome this attitude. The distinction between the mental and the physical is built into our brains (Jack et al., 2013). However, we must try. As Andrew Scull suggests, in the epilogue to this comprehensive and scholarly history of madness, ‘In important respects its [the brain’s] very structure and function are a product of the social environment. … Somewhere in that murky mix of biology and the social lie the roots of madness’.

In addition to telling us about the various ways in which mad people have been treated, we also learn from this book almost everything that people have ever thought and said about madness. I found this fascinating and was particularly struck by the way in which certain themes continually recur. Here are some of the themes that I had fun extracting from the book.

Under and over-civilized forms of madness

The major theme of the book is, of course, the relationship between madness and civilization. Madness, at least from the time of the enlightenment, has typically been defined as a loss of reason. ‘Those unhappy people, who are bereft of the dearest light, the light of reason’, preached Andrew Snape (1675–1742). ‘Distraction … divests the rational soul of all its noble and distinguishing endowments, and sinks unhappy man below the mute and senseless part of creation.’ Without reason the appetites and passions will be released in their full fury. And reason is, of course, the greatest benefit conferred on us all by civilization. Without reason we are no different from other animals.

Given that madness reduced people to the level of beasts, it followed that they should be managed by the techniques developed for training animals. This meant domination through the judicious combination of reward (kindness) and punishment (repression). Such treatment was largely confined to the poor and uneducated classes. However, a well-known exception to this principle was George III. Once it had been decided that his illness was not physical (not brought on by eating too many pears), the mad-doctor Francis Willis was summoned. George’s treatment was brutal, as described by Countess Harcourt, ‘He was frequently beaten and starved, and at best was kept in subjection by menacing and violent language’.

More typically the well-off and educated classes suffered from a different kind of madness to be treated more humanely (and at greater expense). They suffered from nervous diseases, ‘as Spleen, Vapours, Lowness of Spirits, Hypochondriacal & Hysterical Distempers’. These were said to be real diseases rooted in the nerves, so that sufferers could not be stigmatized as malingerers. George Cheyne (1671–1743) referred to such diseases as ‘the English Malady’ (he was Scottish) and showed that these were disorders of the over-civilized. Where all was ‘simple, plain, honest, & frugal, there were few or no diseases’. In contrast, these complaints were to be found in people ‘of the liveliest and quickest natural Parts, whose Faculties are the most bright & spiritual, whose Genius is the most keen and penetrating, and particularly where there is the most delicate Sensation & Taste’.

Pope mocked such superior people, who worship the Queen of Spleen.

Pope was at pains to point out that his own suffering was, in contrast, genuine.Parent of vapours & of female wit,

Who give th’hysteric, or poetic fit,

On various tempers act by various ways,

Make some take physic, others scribble plays.

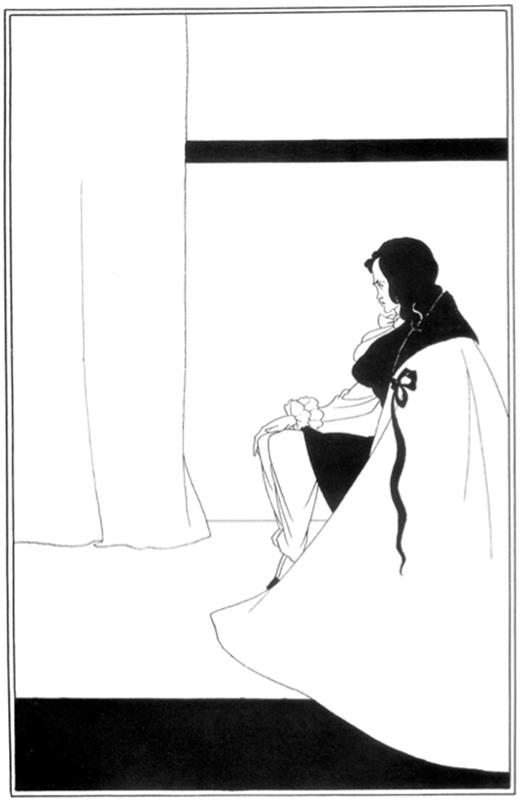

Over the next 100 years the picture of the over-civilized madman continues in a darker mode, reaching its climax in the figure of Roderick Usher (The Fall of the House of Usher, E. A. Poe, 1839). Roderick's mental agitation takes the form of a morbid acuteness of the senses: ‘… the most insipid food was alone endurable; he could wear only garments of certain texture; the odours of all flowers were oppressive; his eyes were tortured by even a faint light; and there were but peculiar sounds, and these were from stringed instruments, which did not inspire him with horror’.

Roderick Usher by Aubrey Beardsley. ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’, 1894.

This was neither the first, nor the last occasion in which a form of madness had become associated with sensitivity, creativity and, as a result, gained a certain cachet. In 1621 Robert Burton had noted that both the intellect and the imagination were stimulated by the melancholy humour. Melancholia became a fashionable disorder among cultivated people, since it appeared to be a disease that afflicted the scholar and the man of genius. Today creativity is still associated with madness, but with mania rather than depression (Jamison, 1996).

In the 1870s a new form of nervousness emerged in the USA: neurasthaenia. This was portrayed as the product of America’s advanced civilization. The electric telegraph and high speed trains, not to mention the decision to allow women to obtain higher education, all put great strain on the nervous system, especially among the professional classes. Expensive ‘rest cures’ were needed to combat this disease.

The fashionable disorder of today is Asperger’s syndrome (Haker, 2014) through its association with sensory overload, scholarly eccentricity, and savant skills. And once again this has been blamed on the ever-advancing technology of modern civilization. In this case the exposure of young men to the Internet (Bell et al., 2015), rather than the exposure of young women to higher education.

What about current attitudes to the other, under-civilized forms of madness? Today the characterization of madness as a loss of reason no longer seems quite so straightforward. This is because the reputation of reason has become somewhat tarnished. Emotion is no longer thought to be the enemy of reason, but is considered to have a critical role in making good decisions (Dolan, 2002). People who are supposedly normal frequently behave irrationally (Kahneman, 2011). It has even been proposed that the main function of reasoning is not to improve knowledge and make better decisions, but rather to win arguments (Mercier and Sperber, 2011).

Scull suggests that madness might be better thought as arising, not from loss of reason, but from loss of common sense. The important aspect of common sense is that it is shared between people. It concerns the norms of behaviour and the folk theories of how the mind works that most people agree about in a particular culture. Such theories need not actually be reasonable, or accurate. Their importance lies in the creation of a cultural consensus (McGeer, 2007). Psychosis is often described as ‘a loss of contact with reality’. But the reality in question is the reality of others. The ideas expressed by the patient are beyond the understanding of others. The patient has no insight into the abnormality of his or her ideas from the perspective of others and is impervious to the opinions of others. The critical feature of psychosis is not so much the irrationality of the belief, but this loss of contact. What is taken to be an irrational belief in one culture may be perfectly acceptable in another.

The villains of the piece

Every good narrative has to have its villains, and it is clear who Scull thinks they are in this story: the mad-doctors, alienists, and psychiatrists, latterly aided and abetted by the pharmaceutical companies. Certainly, across the centuries, many weird and cruel treatments have been applied: drilling holes in the skull, domination and incarceration, infecting with malaria, removal of the teeth and even the stomach, insulin coma therapy, removal of toxic mothers through ‘parentectomy’, and prefrontal leucotomy. In their time all these approaches had some acceptable and apparently rational basis, and all were eventually abandoned because they had no real effect. Of course, a similar story could be told for treatments previously applied to physical diseases, such as blood letting and purging.

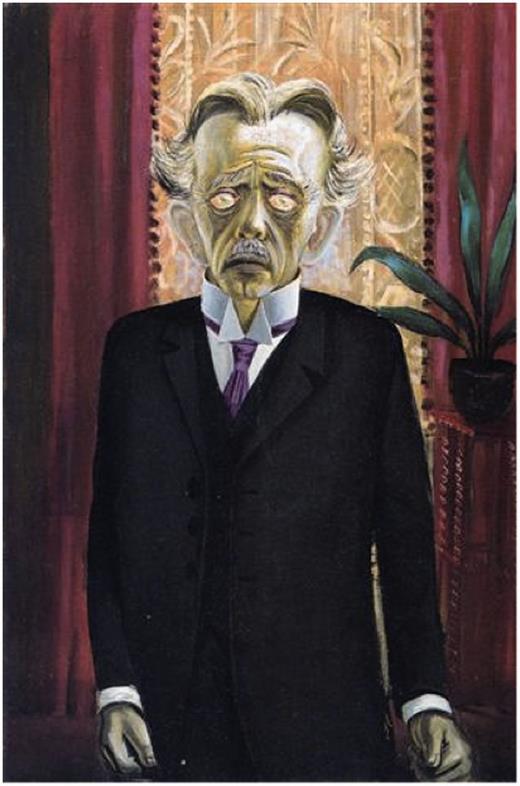

Portrait of Dr Heinrich Stadelmann, 1922, by Otto Dix. © DACS 2015. Heinrich Stadelmann was a German psychiatrist, specializing in hypnotherapy. The portrait was painted while Dix was working on his etchings depicting the horrors of World War I.

Scull is also concerned by the extent to which the mad have been exploited for their money-making potential. In the case of rich patients the transaction is direct, as satirized in Molière’s Le Malade imaginaire. Psychoanalysts seem to have been particularly skilled with such transactions. Edith Rockefeller McCormick became one of Jung’s Dollar Tanten, while Franz Alexander was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation until it was discovered that most of the money ‘had been transferred to the pockets of Herr Doktor Professor Alexander, who aspired to live the life of a German Aristocrat’. But the most notorious was Jacques Lacan, who sometimes reduced the Freudian 50-minute therapeutic hour (but not the fee) to a few minutes in which he might whisper a single parole to the patient. In this way he could see as many as 10 patients an hour.

In the case of poor patients, money could be made from the state by founding mad houses and asylums. These institutions flourished throughout the 19th century and took in increasing numbers of patients. However, by the middle of the 20th century, state support for these big institutions had ceased. Examples of the mistreatment of patients were repeatedly being uncovered and the costs were becoming unaffordable. Patients were released into the ‘community’, but the belief of some that this release from institutionalization would itself be a cure has not been fulfilled.

Money could be made from drugs, also often paid for by the state, through developing palliative, rather than curative treatments, that have to be administered for the rest of the patient’s life and also by claiming that ‘better’ treatments had been developed (e.g. the atypical anti-psychotics), once the patents on the earlier treatments had lapsed (Tyrer and Kendall, 2009).

Of course, all these critiques beg the question of how to deal with the suffering associated with madness, for patients, relatives, and carers. Desperate people will always find someone who claims to have the answer.

The sharpest criticism of psychiatry made by Scull is the suggestion that our understanding of madness and our ability to treat it have hardly advanced since the Middle Ages. This criticism is unfair. Many of us believe that some progress has been made—even sedation by drugs would seem more humane than straightjackets or chains. But, to some extent, psychiatrists have only themselves to blame given how they define their domain as ‘mental science’.

Many years ago I worked in the Psychiatry Unit at the MRC Clinical Research Centre in Northwick Park Hospital. Our brief was to elucidate the biological basis of schizophrenia. At that time the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III stated that a diagnosis of schizophrenia was appropriate only if ‘the disturbance is not due to … Organic Mental Disorder’. In its turn ‘Organic Mental Disorder’ was defined as, ‘psychological or behavioural abnormality associated with transient or permanent dysfunction of the brain’. In other words, if we found a brain basis for schizophrenia, it would cease to be schizophrenia. This exclusion criterion was removed from subsequent versions, perhaps in part because of the increasing evidence of brain abnormalities in schizophrenia (Johnstone et al., 1976).

This specific example illustrates a more general problem. Psychiatric illnesses are typically defined (as on the website of the World Health Organisation) as ‘disorders that manifest as abnormalities of thought, feeling, or behaviour’. This is in contrast to neurological diseases, which are ‘physical diseases of the nervous system’. This distinction lies behind the quip that neurologists take all of the curable diseases and leave psychiatrists with the ones that cannot be helped.

‘General paresis of the insane’ is a striking example of a psychiatric illness that became curable. In the 1880s general paresis of the insane, as Scull notes, accounted for ∼20% of the male patients admitted to asylums. Symptoms included mania, delusions and dementia. Originally it was thought that general paresis of the insane was a severe consequence of any kind of insanity caused by a weakness of character or constitution. However, by 1822 Bayle had demonstrated that it was a specific disease entity associated with brain lesions (chronic arachnitis). By the end of the 19th century the disease was increasingly linked with syphilis and, in 1913, syphilitic spirochaetes were identified in the brains of patients demonstrating conclusively that it was caused by syphilis. After World War II, the use of penicillin to treat syphilis had almost eliminated general paresis of the insane. This was a dramatic success for research. Indeed, it was such a success that this form of madness is now effectively invisible. In Wikipedia it is characterized as, ‘originally considered a psychiatric disorder’.

More recently there have been similar advances in our understanding of many other disorders previously associated with madness, such as epilepsy, dementia, and certain forms of mental deficiency such as Down syndrome and Rett syndrome. Rett syndrome is now known to be caused by mutations in the gene MECP2 and, at least in mice, can be reversed by restoration of gene function. Rett syndrome has been removed from DSM-5, the most recent edition of the American psychiatrists’ diagnostic bible, because it has a known genetic cause.

Evidence for this changing attitude to mental disorders can be found by looking at the topics of papers published in neurology and psychiatry journals. Borrowing an idea from the anonymous blogger, Neuroskeptic, I compared numbers of publications in the British Journal of Psychiatry (previously known as the Journal of Mental Science) and Brain. Between 1910 and 1929, ∼90% of the papers on epilepsy were published in the psychiatry journal, but by 1990–2009 this had fallen to ∼10%. Similarly, for dementia the fall over the same period was from ∼95% to 40%. In contrast, the psychiatry journal continues to publish the vast majority of the papers on schizophrenia. Of course, the psychiatrists are still called on to cope with the behavioural problems associated with the ‘neurological’ disorders.

Neuroscience research has had considerable success in elucidating and sometimes curing various disorders, but after each success the disorder either becomes invisible or ceases to be considered an example of madness. So it seems strangely inevitable that madness can only ever be associated with disorders that we do not understand. It is not the patients’ reason that has failed, it is ours. But then reason has never been a strong point with mankind, however civilized.

References